By Jauhara Ferguson, Department of Sociology and Brenton Kalinowski, Department of Sociology

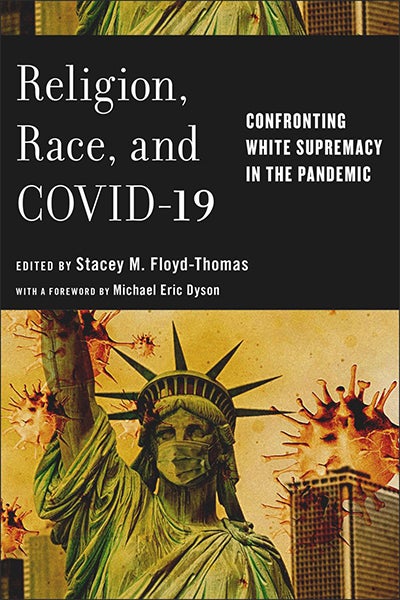

Stacey M. Floyd-Thomas’s (2022) edited volume Religion, Race, and COVID-19: Confronting White Supremacy in the Pandemic is dedicated to examining the multiple intersections between religion and race during the COVID-era. The volume includes 11 articles from authors mainly out of the humanities, that emphasize the increased importance of religion at the intersection of racial inequality and racism during the pandemic. In this book Floyd-Thomas calls for faith communities to build outside of religious infrastructures and move from freedom of religion to what she calls “freedom as religion.” Though the articles range in topic, the book has several key takeaways. First, the book stresses the impact that the pandemic has had in becoming a magnifying lens through which to see intersections of racial and gender inequality more clearly. Because of this, COVID-19 has become used as a tool to promote structural inequities and injustice. Second, the impact of COVID-19 has laid bare the ways that religion and religious communities both perpetuate inequality, and challenge inequality in subversive ways. The lack of embodied community during the pandemic has created new opportunities for marginalized groups to promote their virtual spaces of gathering, and to encourage spirituality rooted in justice. At the same time, religious structures and meanings are being challenged, and generational divides are taking shape within Black Christian communities. As Melanie Jones writes in Chapter 2 of the book “The truth is that millennial faith looks different, with less emphasis on building religious institutions and greater interest in social change that inspires individual and communal liberation.” Third, the book emphasizes racial solidarity over racial reconciliation. In this instance racial solidarity means a focus on the structural inequalities and how to combat them. In contrast, racial reconciliation is more closely tied with the perspective that racial inequality stems from a lack of faith rather than being a systematic part of our society. In Chapter 7 of the book Miguel De la Torre calls out some Hispanic pastors for simply adopting the same frameworks for thinking about race through the lens of a white racial reconciliation framing or as he calls them unapologetically “brown faces with white voices.” Fourth, the book highlights the way COVID-19 has reintroduced various forms of White supremacy into the public. These forms of White supremacy emphasize individualism and religious liberties for their own, at the expense of the wellbeing and freedom of non-White others. Marla Frederick writes in Chapter 11 that the idea of religious freedom can be used by white Christians and political leaders to justify a lack of response to the pandemic while not acknowledging the religious freedoms of others. The book includes historical context for the multiple ways that White Christian communities have harmed non-White communities physically and spiritually. Because of this, the book’s final call is to encourage non-White communities to invoke their own spirituality and belief to find new forms of coping to ultimately come to a place of liberation independent from the existing structures of racism and inequality.

The book has bold ambitions, and ultimately succeeds in producing a commentary on the religious and racial implications of the pandemic. However, the book is not without critique. While the book makes importance theoretical contributions, it could be enhanced with more empirical observations on the impact of the pandemic within religious spaces. More could be done to understand how non-White religious communities responded to the health challenges of the pandemic. While the beginning chapters discussed the move from physical structure of the Black Church to more online communal Black womanist spaces, it did not discuss the potential or realized drawbacks of only building community online. Further, the book did not examine the place or value of embodied community for non-White groups in the pandemic era. The book also balances three major topics- religion, race, and COVID-19- but at times succeeds in focusing on only one or two. More could be done to think about the intersection between these three topics and how they shape our understanding of White supremacy. Overall, this book is a good steppingstone to help scholars of religion and race consider how the pandemic has ushered in a new era of faith and racial justice.